Why We Are A Vegan Company.

There are many reasons folk make food choices, in the case of becoming vegan these vary from animal welfare, to health, to planet welfare. At Local Dehy we, like most vegans, would say ‘for all those reasons’. We have been asked if we intend to, or could do meals containing meat in the future. The short answer is ‘no’, but let me explain…

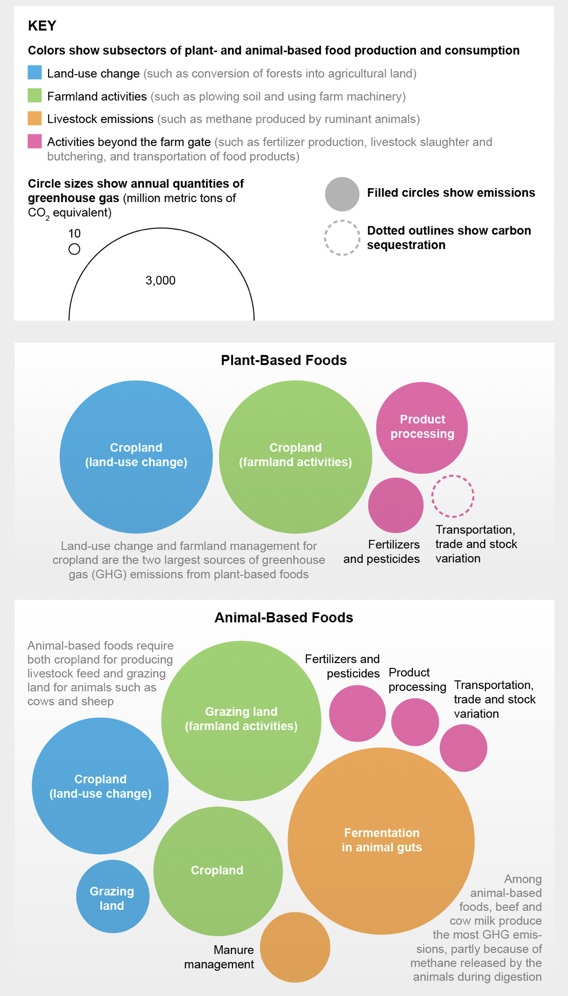

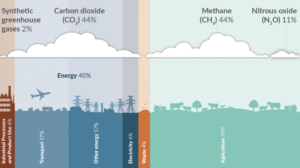

The long answer is that a large part of our vegan ethic is for environmental considerations. Global production of food is responsible for a third of all planet-heating gases emitted by human activity, with the use of animals for meat causing twice the pollution of producing plant-based foods.¹

Meat production has two kinds of global heating impacts, firstly the gases released by farming animals which is dominated by the powerful greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide. And secondly, the large-scale deforestation for grazing and land to grow feed which reduces biodiversity and natural carbon sinks.

Source: “Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Animal-Based Foods Are Twice Those of Plant-Based Foods,” by Xiaoming Xu et al., in Nature Food. Published online September 13, 2021

Globally it is estimated that more crops are grown to feed animals than for people. When we consider that the amount of energy needed to rear an animal far exceeds the energy received back from its consumption, it’s clear this is a hugely inefficient system. A study of carbon costs published in Nature² found that one kg of soybean protein costs 17kg of carbon dioxide, whilst one kg of beef protein cost 1,250kg of carbon dioxide. Feeding the crops and water directly to people and ‘cutting out the middle cow’ is a more efficient use of land and resources. Also, as crops use fewer hectares to produce the same amount of energy [compared to livestock] a vegetable-based diet could leave more land available for rewilding, using the mass restoration of nature to draw down carbon from the air. This is an idea that George Monbiot, an outspoken environmentalist, claims offers perhaps the last remaining chance to prevent more than 1.5C, or even 2C, of global heating. “Saving the remaining rainforests and other rich ecosystems, while restoring those we have lost, is not just a nice idea: our lives may depend on it”

Interestingly, in the plant-based sector, rice farming is the top contributor to greenhouse gases, and it is the second-highest contributor among all products. Rice’s relatively high ranking comes from the methane-producing bacteria that thrive in the anaerobic conditions of flooded paddies.

It is a complicated argument to say ‘eat less rice’ as a solution to climate change, as for large populations of the world – namely Asia – rice is an important source of basic nutrition and can be grown in places other crops can’t. Whilst some might argue the same for animal products, eating meat has increased in countries with increased wealth, not decreased wealth, signalling it is the food choice of the richest countries, not the poorest.

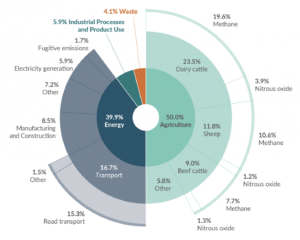

Here in New Zealand we have a different carbon profile from many other developed economies, namely in our agriculture contributions. The Ministry for the Environment Greenhouse Gas Inventory / Te Rārangi Haurehu Kati Mahana a Aotearoa 1990-2020 ³ showed the 2 biggest sectors were Agriculture 50%, and Energy (including transport) 40%. For comparison in the EU in 2020, 11.78% of emissions were from Agriculture.⁴

The specific emissions can be broken down into sub-categories and gas types shown in the diagram. Our emissions from dairy far exceed all other Agriculture, in the 2020-21 season there were 4.9 million cows in NZ. Their collective burping and farting takes them to the top of the emissions polluting chart.

There are other obvious issues of high cattle numbers aside from carbon emissions. As herd numbers increase as does the amount of nitrate runoff into our rivers; the cows’ urine and feaces, as well as the excess chemicals from fertiliser for their feed leach into waterways. Cattle urine and fertiliser both contain nitrogen. It makes grass grow, but if there’s more nitrogen than the grass can use, it leaches into groundwater. If it makes its way into rivers it promotes the growth of plants in the water and contributes to algal blooms, reduced oxygen levels and reduced light. This has left 75% of pastoral land with a D or E rating for swimming due to E. coli counts. Too much nitrogen in water is also bad for fish, of which three-quarters of New Zealand’s fish species are at risk of extinction, which Victoria University of Wellington’s Dr Mike Joy says is “higher than I can find for any country in the world”. In Canterbury, the problem is exacerbated by the type of soil. “They’re very gravelly, sort of loose soils that that water flows through really, really quickly. What’s happening is the urine, highly nutrient laden, almost totally nitrogen, urine going through those soils and appearing in the aquifers,” Joy says.

For a bit of balance, DairyNZ states that the dairy industry brought the country $20 billion in exports (95% of all our dairy is exported) and employed 50,000 people. DairyNZ also state farmers are committed to having fewer cows with an increased yield to become more sustainable.⁵ There is currently work underway to create an animal feed that makes the cows burp less reducing methane emissions. Reductions in herd sizes, and technology inception may see a future reduction in emissions…as would less consumption of dairy. This is a complicated discussion space!

In summary, choosing a plant-based diet can be one way to help reduce your impact on the environment; on average halving the emissions in your food production; you can grow more plant-based products for the same energy input when compared to meat, and you can reduce the amount of carbon per kg of protein. Fewer animals would also reduce agricultural land use providing increased possibilities for rewilding.

However, giving up meat and dairy alone can’t be viewed as a magic bullet to help NZ reach its COP26 targets. Reducing our impact is multi-faceted, so as well as altering the way we eat we need to be mindful of the bigger picture and have a holistic approach to our impacts. Remember that food production is 30% of total world emissions so that still leaves another 70% to work on.

There are many other ways in which we can have an effect on the health of our whenua; things like riding a bike to get your groceries, growing veggies at home, ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ (in that order) everything from clothes to packaging. Also supporting small local NZ companies who place social and environmental sustainability at the forefront of their operations, can all have a small positive impact on Papatuanuku. If everyone in NZ made a small impact it would add up to a rather large 5 million people impact!

NEVER UNDERESTIMATE THE AGENCY WE ALL HAVE TO MAKE CHANGES!!

References:

¹ A comprehensive paper recently published (2021) by the University of Illinois in ‘Nature Food’ used data on 171 crops and 16 animal products from more than 200 countries, along with computer modelling, to calculate the amounts of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are contributed by individual elements of the global food system, including consumption and production. They found that the use of cows, pigs and other animals for food, as well as livestock feed, is responsible for 57% of all food production emissions, with 29% coming from the cultivation of plant-based foods. The rest comes from other uses of land, such as for cotton or rubber.

Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Animal-Based Foods Are Twice Those of Plant-Based Foods,” by Xiaoming Xu et al., in Nature Food. Published online September 13, 2021

² Searchinger, T.D., Wirsenius, S., Beringer, T. et al. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 564, 249–253 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0757-z

³ The official annual estimate of all human-generated greenhouse gas emissions and removals in Aotearoa.

https://environment.govt.nz/publications/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-inventory-1990-2020-snapshot/

⁴https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/data-and-maps/data/data-viewers/greenhouse-gases-viewer

⁵https://www.dairynz.co.nz/news/more-milk-from-fewer-cows-trend-continues-in-a-record-year-for-nz-dairy-industry/

HOME COMPOSTABLE V’S PLASTIC PACKAGING: How did we choose?

In Jan 2022 we moved away from the traditional petroleum-based plastic thermal pouches to using plant-based home compostable packaging. How did we make this decision?

When we first began our journey we used petroleum-based plastic pouches only as was the standard practice in the sector. As a company with an environmental heart this packaging never sat particularly ‘right’ with us, especially considering the single use nature of the product. I spent many years searching for alternatives. Eventually we came across Econic, who were providing home compostable packaging. We decided to run this alongside our plastic pouches to gauge the desire for this in the market. It was a success, and in the first year it made up half of all sales. The next year, with overwhelming support from our customers, we made the decision to discontinue the oil-based pouches.

When looking for alternatives we wanted to find a plant based product made from renewable resources that could legitimately ‘disappear’ back into the earth with the least amount of inconvenience, and zero harm to our land. Surprisingly, it wasn’t actually that easy! Whilst there is an increasing market for ‘green’ packaging, many of the products need to be composted in an industrial facility with very specifically managed environmental conditions. Of which, there are only 2 community-accessible facilities in New Zealand. To complicate matters these items can’t be recycled via our normal recycling scheme either. So, it was important for us to find a product that did not need to be industrially composted.

When looking for alternatives we wanted to find a plant based product made from renewable resources that could legitimately ‘disappear’ back into the earth with the least amount of inconvenience, and zero harm to our land. Surprisingly, it wasn’t actually that easy! Whilst there is an increasing market for ‘green’ packaging, many of the products need to be composted in an industrial facility with very specifically managed environmental conditions. Of which, there are only 2 community-accessible facilities in New Zealand. To complicate matters these items can’t be recycled via our normal recycling scheme either. So, it was important for us to find a product that did not need to be industrially composted.

Currently, petroleum-based pouches that can hold boiling water to rehydrate the meals are used by every major company in the sector. They can hold hot water which makes them ultimately very convenient for the consumer for rehydrating the meals, but more inconvenient when it comes to disposal. For the end-of-life stewardship of this pouch to be fully realised they have to be washed, cleaned and dry, and then taken to, or sent to, the soft plastic recycling scheme. Now, whilst there may be many a responsible kiwi tramper out there, we think that at least some of the 4 day-old food pouches that were stuffed away into packs might not make the washing pile and delivery to the scheme, and instead become landfill. If you are keen there is plenty of information about the NZ soft plastic scheme here: www.recycling.kiwi.nz.

Currently, petroleum-based pouches that can hold boiling water to rehydrate the meals are used by every major company in the sector. They can hold hot water which makes them ultimately very convenient for the consumer for rehydrating the meals, but more inconvenient when it comes to disposal. For the end-of-life stewardship of this pouch to be fully realised they have to be washed, cleaned and dry, and then taken to, or sent to, the soft plastic recycling scheme. Now, whilst there may be many a responsible kiwi tramper out there, we think that at least some of the 4 day-old food pouches that were stuffed away into packs might not make the washing pile and delivery to the scheme, and instead become landfill. If you are keen there is plenty of information about the NZ soft plastic scheme here: www.recycling.kiwi.nz.

Whilst soft plastic is a very recyclable product, studies have shown that 91% of all plastic ever made still exists in its original form (in landfills or the ocean) and that only 9% of it has ever been recycled. The reasons behind this are multiple and include accessibility to schemes, collection, batch contamination from dirty used plastics, and processing capacity. Interestingly, these are the same issues that plague the reusing of bioplastics.

We wanted to find a product that didn’t need any special treatment, that didn’t need to be cleaned and dried, that didn’t need to be sent away to be recycled, and that was the least likely to end up in landfills. After weighing up the pros and cons of home compostable v’s soft plastic we believe that the best product stewardship is to have a product that can easily be disposed of without the need for additional industrial processing. This meant using home compostable packaging.

Whilst there are currently no New Zealand standards for the term ‘home compostable’, international standards have been recognized and adopted. Our packaging from Econic meets these certified standards for home compostability, namely, the European and American standard EN 13432 and ASTM6400, as well as the European and Australian standard, OK Compost Home (Europe) and AS5810 (Australia). It is made from a combination of compostable films derived from sustainably-managed renewable resources and contains no PLA. This means the New Zealand government recognises our packaging has been certified for disposal in home compost.

We believe that products made from natural resources with the ability to be regenerated back into the environment without contaminants is currently the best packaging option for our product. We need to reiterate that our packaging needs to be put into a home compost or worm bin as it will not compost in landfill, and it is not currently accepted in kerbside food and garden waste collections.

A final point I want to make here is that the best form of packaging is no packaging!

So whenever, and wherever you can, ditch the wrapper – compostable or plastic.

Note: I have written further blogs on the issues and considerations of both plastics and bioplastics with more detailed information than I could incorporate here which also shaped our decision to use home compostable packaging. Coming soon.

LAKE HĀWEA, HOME OF LOCAL DEHY

Local Dehy is located in Lake Hāwea, nestled in the foothills of Tititea, Mount Aspiring National Park. Lake Hāwea is named after a Māori tribe who preceded the Waitaha people in the area. This lake and mountains inspire us to be our best selves. They humble us in their vastness and remind us to tread lightly. Legends of Papatuanuku – Mother Earth – remind us of our Kaitiakitanga – guardianship responsibilities for these wild places.

The shores of the Lake are surrounded by small hills that provide some great hiking opportunities with world-class views. Trails head up from the lakeshore to several of the peaks. On the western shore is the most well-known of the trails, Isthmus Peak. There are expansive views of the Ka Tiritiri o te Moana – the Main Divide, from its summit. At the tip of this peninsula, you can also see both Lake Hāwea and also Lake Wanaka, and separating them, a small piece of land called The Neck.

It is important to recognise that two hundred years ago, a visitor to the Lake Hāwea side of the Neck, north of the Lake Hāwea township, would have found a Maori village called Manuhaea. It had, perhaps, 20 houses surrounded by gardens of potato, turnip and other vegetables and had easy access to a freshwater lagoon. There was an abundance of weka, kakapo, kiwi, kea and kaka, and the streams were full of ”tuna” or eels. It was central to an extensive network of walking trails linked to all the major settlements and resources of the South to the West Coast. This area is now in the governance of DOC.

Photo: Isthmus Peak far left, the Neck centre left, McKerrow Range centre, and the Hunter Valley far right.

The most captivating mountains are those at the head of the lake, The McKerrow Range. These are the biggest mountains at Lake Hāwea, and the ones that dominate the skyline when standing on the pebble beach in the township. Sentinel Peak is the largest of these visible.

On the eastern side of the lake, a winding dirt road is a jump-off point for Grandview and Breast Hill. The Te Araroa passes through this area, and the DOC hut book at Pakituhi Hut is full of praise for its stunning location. After a hill walk a refreshing swim can be had on a hot day in the glacial-fed waters of the Hunter Valley.

Local Dehy takes responsibility for our impact on our beautiful corner of the world. Our environmental governance seeks to minimise harm throughout our processes and extends to product stewardship in the end-of-life cycle of our packaging.

When we visit these magical places we can all play our part in our responsibilities towards this whenua. The air, the mountains and the water are our lifeblood, destruction of them is destruction of us. We can all endeavour to try a little bit harder to protect our natural resources. Be a champion of the protection!